[This is the third in a series of posts on the shooting of Nightmare Cinema’s “This Way to Egress.” You can find the previous installments here and here. The film is available to stream on Freevee and Tubi or to rent/own on Amazon, Apple, and Vudu.]

In his essay “The Effect of Effects” (2008), critic Roger Ebert praises the cinematic illusions created for films like The Thief of Bagdad (1940), The Wizard of Oz (1939), and the original Star Wars (1977). “They had heft and presence,” he wrote. “The filmmakers went to the trouble of model-making instead of slapping in some CGI. Nor did they dwell on their work; the shots were only held long enough to make their point.”

Director David Slade has expressed similar objectives when discussing his decision to use practical elements in “This Way to Egress” (see previous post). That’s not to say digital enhancements weren’t employed, but that when they were, they were used to augment the look of physical locations, props, and prosthetics.

And to Ebert’s point about shots only being “held long enough to make their point,” let’s take a moment to consider the practical elements that went into creating a split-second of violent horror at the film’s climax, a moment that occurs when Helen returns to the office of Dr. Salvador (Adam Godley) to find him sneering down through a swirl of flying ash. His white lab coat is black with grit; his once kindly face, grotesquely deformed. Beside him, covered in filth but otherwise unchanged, are Helen’s sons Chris (Macintyre Sweeney) and Eric (Lucas Barker).

You know what happens next. You’ve seen the film. (And if you haven’t, the links are above. Take a look. I’ll wait.)

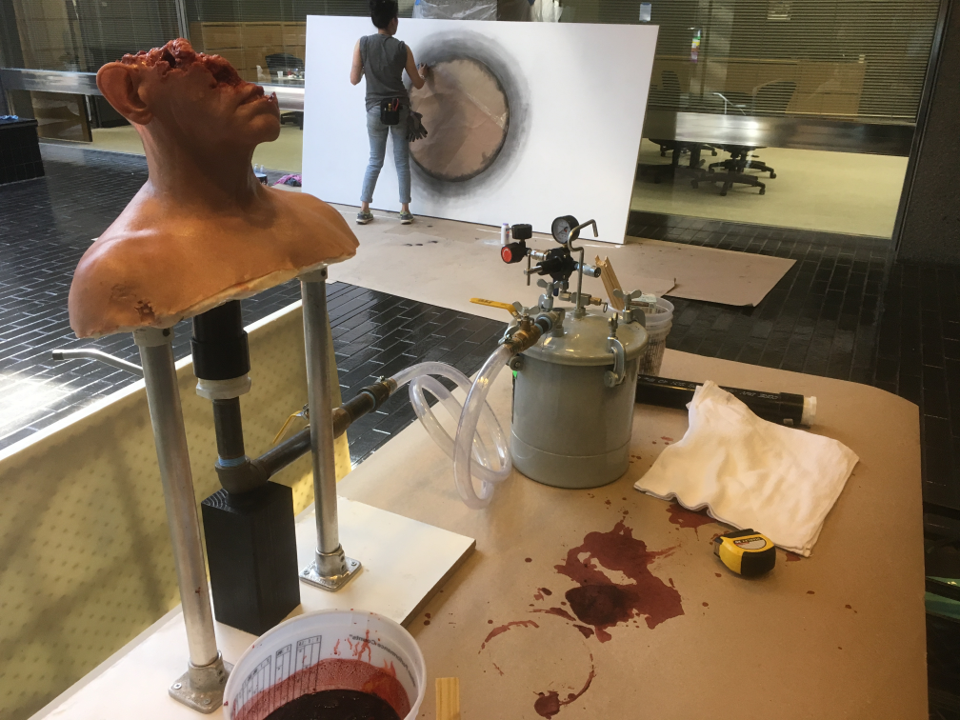

Central to what you see in that moment of carnage was a life-size prosthetic of Salvador’s head, partially cut away and connected to a pressurized tank of fake blood (see the photo atop this page). Glimpsed for barely a frame or two as a stand-in for Adam Godley, the prosthetic is enhanced by copious amounts of Kensington Gore, launched from an off-screen catapult and directed at a glass wall that runs the length of Salvador’s office. And since the window was part of a real office building and not a green-screen studio, the crew had to spend the better part of an afternoon covering the surrounding floor, furniture, and walls with plastic sheeting to control the spatter.

The shot required multiple takes. But I think the results speak for themselves.

Similar attention to detail went into selecting the various props that appear throughout the film. Consider, for example, the wall-mounted diplomas hanging on Salvador’s wall: one, an honorary degree in the field of paranormal studies; the other, a bachelor’s from “the University Academy of Psychology.” We glimpse these bits of world-building only fleetingly. We don’t have time to read them, nor are we intended to. Like many of the film’s practical elements, they contribute to the subliminal reality of “Egress” without being dwelled upon.

Likewise, the single-use medical device that Helen finds in her purse–the innocuously labeled Ticket Out–comes in a hermetically sealed pouch bearing a warning label printed with text that in part resembles the grit and ash that is overrunning the world of “Egress.” We see it momentarily as she opens the pouch—one of a number of shots that are “only held long enough to make their point.”

And then there’s a sequence that was shot but didn’t make it into the film’s final cut. It involves a tiny spider with oversized fangs. You can read about it in “Lost Spider Scene” and “The Spider from Egress.”

Next time, we’ll look at how practical effects transformed an ordinary men’s room into the setting for one of the most harrowing scenes in the film.

In the meantime, here’s a clip of that bloody catapult in action.

Hit play … then grab a mop.

Leave a Reply