It’s piped into your home, available at the flick of a switch, provided at a monthly charge, and pretty much taken for granted.

It’s a utility. You know—like gas, electricity, phone service, internet … and entertainment.

That was one of the opening points made by Mark Gooder on this week’s AFM panel The Global Perspective: Breaking the Boundaries of Today’s Film Marketplace. As he explained it, accessing entertainment (movies, television shows, music, books) has “become the equivalent of turning on the gas or the electricity.”

It’s a startling observation, particularly to those of us who remember days when moviegoing was an event—something attended rather than delivered.

So what are the implications for writers (now called “content creators”) striving to compete in the age of utility entertainment?

According to panel moderator Steven Gaydos, who started his career with Roger Corman in the 70s and now serves as Executive VP of Content at Variety, it comes down to thinking about content in binary terms. That is to say, your film either “has value, or it has no value.” The light either comes on, or it doesn’t.

The challenge, according to Gaydos, is to find a way to make “storytelling special again.” But how?

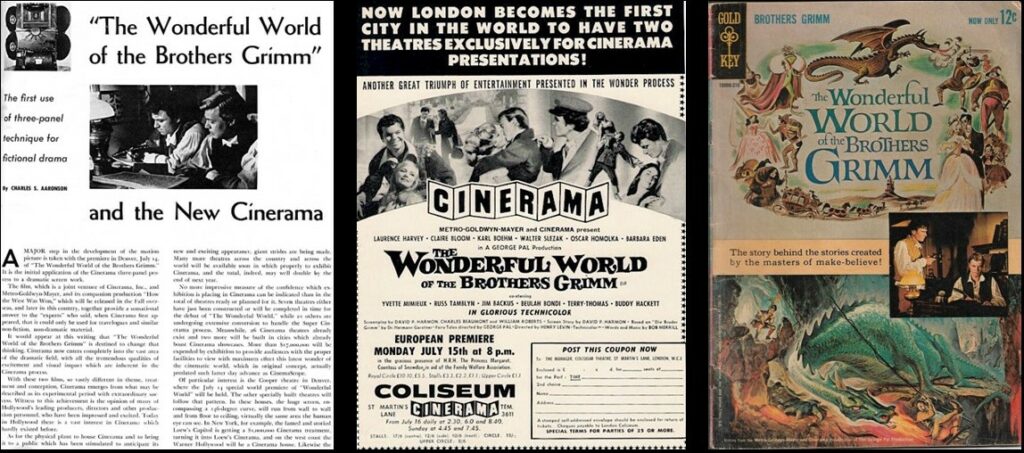

All this got me thinking about how audiences used to experience major forms of entertainment in three distinct phases, starting with advance notice (which usually appeared in print media). It might have been a preview story in a major magazine, a giant ad in the newspaper, a mass-market novelization or comic book adaptation. Something like these (for the 1962 roadshow picture The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm):

Each one of these built anticipation, giving the audience a chance to imagine the film before actually seeing it. And when the film did arrive, audiences had to go out to experience it. It was a commitment. Something that had to be planned for. An event!

And the event was the second phase, when the audience actually saw the film, which involved making plans, going to a theatre, standing in line, and sitting for a couple hours in an auditorium full of strangers. No hitting pause. No off switch. It was a commitment.

And after that commitment came the third phase: reflecting, considering the experience, replaying it in memory and conversation. Interestingly, as filmmaker David Slade recently told me, that third phase is when you actually see the film, when the whole experience becomes part of your inner landscape and surrounding culture. Films used to be considered. Today, they’re simply replayed … or more often forgotten as we move on to the next title in our queue.

Clearly, the world has changed. The old system that relied on print media, roadshow events, and limited access is gone. But lamenting the loss and seeking ways to bring back those good old days will likely only lead to frustration.

“For my generation, there’s a danger or tendency to see everything through the prism of how it was,” Steven Gaydos said. “And I think that’s really a rotten way to see things. But […] it’s hard to give up the nostalgia for something that made sense.”

Further illustrating the sentiment, panelist Syrinthia Studer pointed out that the good old days weren’t quite as rosy as they look in hindsight. She then told the story of a time when a new CEO at Paramount presented his team with a list of negative headlines about the state of filmmaking. “Things like Film is Dead! Every negative headline you can possibly imagine.” And everyone agreed. The situation was dire. Filmmaking was doomed. But then the CEO revealed that the headlines were not contemporary. They were decades old, or as Syrinthia put it, they were “from the dawn of time!”

Syrinthia’s takeaway: “With every job I learn something new. The industry changes, then I change. And that kind of adaptability is what we need.”

We may no longer have print media in the form of newspapers to build anticipation with preview features and full-page ads. Instead, we have Tic-Tok, YouTube, Rotten Tomatoes. And you know, it’s a funny thing, but I bet there’ll be a time in the future when storytellers–whether you call them scops or content creators–will look around and lament that those avenues of publicity have been replaced by something new and incompatible with the old ways of doing business.

In the meantime, I’m encouraged by the assessment that Jeff Greenstein shared on the panel What Audiences Want (see previous post): “The one thing that hasn’t changed is the importance of storytelling. The three most important things in a movie are story, story, story.”

Echoing that point, Steven Gaydos summed up the solution by emphasizing the importance of tenacity. Or as Christian Vesper put it at the end of the discussion, “I think you just have to keep writing and making the projects you believe in.”

In other words, scop on!

Leave a Reply