The Resilience of Frankenstein.

[The following is a transcript of my TEDx talk on Mary Shelley and resilience, presented in Rea Auditorium, Sewickley PA, May 11. 2024. The video is currently streaming on the TEDx Channel.]

It occurs to me that when I think about resilience, I think everything I’ve learned comes from a novel written by a teenage girl over 200 years ago.

The novel is Frankenstein; the teenage girl, Mary Shelley (she was Mary Godwin then). And what they have to teach us has as much to do with what the novel itself, which is the story of a brilliant young man who lacks the resilience to pursue his dreams, as it does with the tenacity of the young writer who refused to give up on hers.

Mary was eighteen when she decided to become a novelist, and this was a daunting undertaking for anyone in the 19th century, especially a young woman. Back then, novelists were men, and the few exceptions wrote romances and comedies.

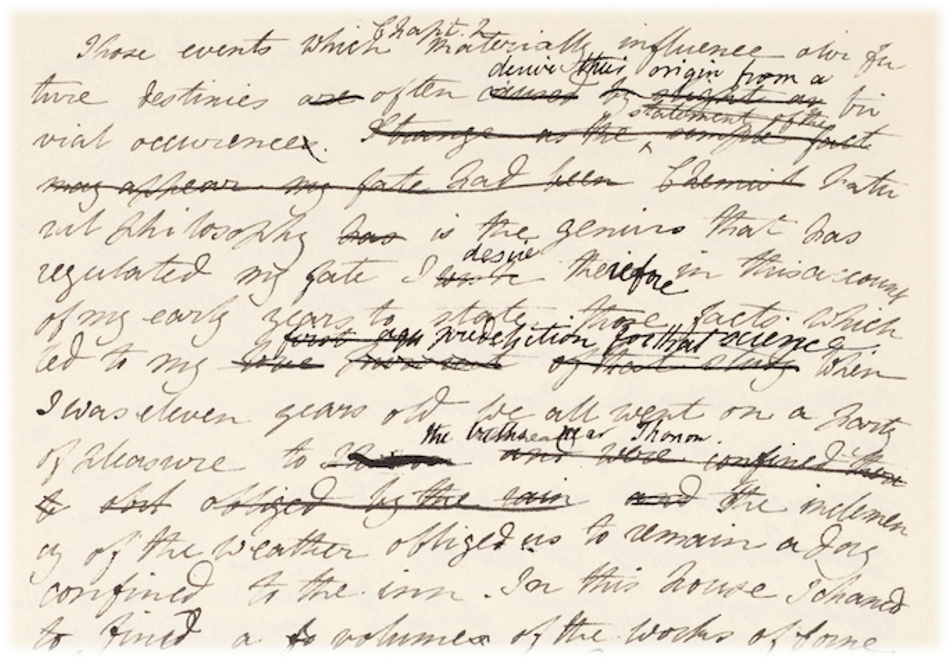

But Mary wanted to write something that defied category. She wanted to write something that no writer, man or woman, had ever dealt with before. And so while traveling through Europe, she began working on the manuscript that became Frankenstein.

Traveling through Europe.

It sounds romantic, but the truth is she was essentially homeless, caring for an infant child and on the run from creditors because the man she was in a relationship with had such a precarious grasp of finances that he had left them both deep in debt. And yet over the course of that year, Mary completed the manuscript and submitted it to one of the top publishers in London. And within only three days, that publisher rejected it.

Resilience! She submitted it again. Rejected again.

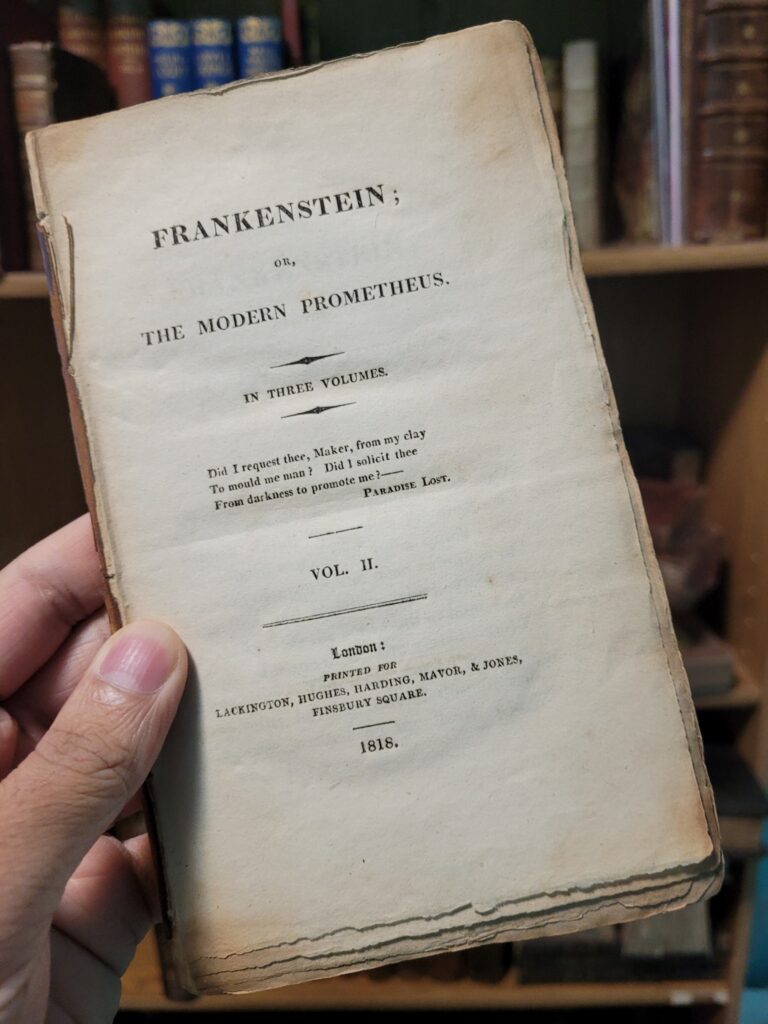

She finally submitted Frankenstein to a publisher that agreed to take it, provided she did not put her name anywhere on the book (because who would buy such a book written by a woman?), and provided she accept no payment upfront, but only a small percentage of the profits of the book sold.

It was hardly a windfall.

Only 500 copies of the book were printed, and those didn’t sell. Nine months later, book sellers in London were running ads trying to unload unsold copies of Frankenstein.

And the reviews?

One reviewer wrote, “Frankenstein is a horrible and disgusting absurdity.” And another dismissed it entirely by saying, “The author of this is, we understand, a female. Well, that is the prevailing fault of the novel.”

But perhaps the most damning criticism came from fellow novelist William Beckford, who wrote, “Frankenstein is the foulest toad stool ever to have sprung up from the wreaking dungill of our current times.”

She did not give up.

If that first book wasn’t going to make her a successful novelist, she was going to write a second.

She began working on the second, and she finished it within a few years, even though tragedy struck: the death of her three-year-old child by malaria, the death of her husband by drowning.

And she still finished the book.

It came out in 1823. But alas, it was no more profitable for her than Frankenstein was. And by now, Frankenstein was forgotten.

Or so she thought.

In 1823, the same year that her second novel came out, something remarkable happened.

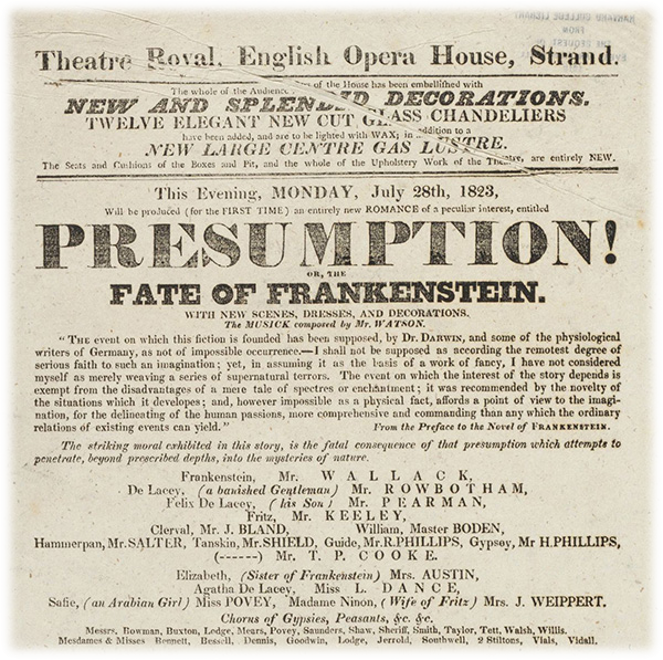

An Unauthorized Adaptation.

She was back in Europe when she received a letter from home letting her know that an unauthorized adaptation of her first novel was about to be performed at the English Opera House in London.

This was news to Mary.

Back then, playwrights could adapt a novel without the author’s permission, and the author was not entitled to any payment for the use of the intellectual property. But Mary was delighted that her forgotten, despised first novel was going to get new life on the stage.

But unfortunately, as with the novel …

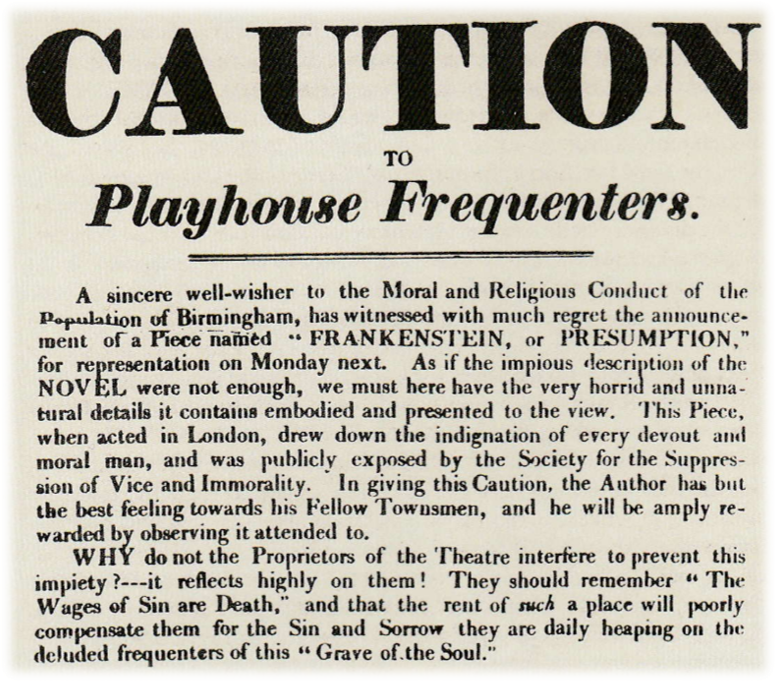

The play generated a wave of derision.

The London Society for the Prevention of Vice and Immorality wrote, “Do not go to see this monstrous production Frankenstein. Do not take your wives and families. The novel itself is an immoral trifle. It deals with a subject, which in nature, cannot exist.”

That comment, “Do not take your wives,” was probably a result of reports that “ladies were fainting” at productions of Frankenstein, and a general “hubbub” was ensuing.

Nevertheless, despite these reports, or maybe because of them, the play was a resounding success, and Mary returned to England to discover that after years of laboring in obscurity, she was finally a celebrated author. Writing to a friend, she said, “Lo and behold, I found myself famous.”

The novel was rushed back into print, and this time it had her name on the cover (she was Mary Shelley now), and it included a new introduction by Mary in which she wrote, “I bid my hideous progeny to go forth and prosper.”

And did it ever prosper!

The book sold briskly. More adaptations followed. And today, Frankenstein remains in print. It’s one of the great works of world literature and has earned Mary Shelley a place in the pantheon of the world’s greatest writers!

And think of all the spin-offs: books, plays, television shows, movies, Halloween masks, bobble-headed dolls. It’s hard to imagine that there could be a world in which Frankenstein doesn’t exist, and yet it almost didn’t.

If Mary Shelley had let conventional wisdom make her believe that a woman could not write a novel, if she had let personal difficulty get in the way of her starting and finishing the book, if she had let those terrible reviews convince her that maybe it was better just to be the anonymous, unknown author of a derided first novel, then we would not be talking about her today.

Principles of Resilience.

Today, Frankenstein is considered the prototype of the modern science fiction novel. So perhaps it is appropriate that, a little more than a hundred years after Mary Shelley returned to Europe to find herself famous, the famous 20th-century science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein put forth his principles for becoming a successful writer, principles that seem to reflect the resilience of Mary Shelley.

Heinlein said, If you want to be a successful writer, you must first write. And then you must finish what you write. You must submit what you write for publication. And you must continue to believe in your dream and keep it in submission until it is sold.

Now taken together, these principles can relate to any endeavor.

The world may try to convince us that our dreams are not worth pursuing. But if we persevere, if we perhaps learn from the novel Frankenstein, the story that it tells of a young student who has the desire to create something greater than himself and discovers, after two years of work, that the initial results fall far short of expectation. He deems himself and his creation a failure. He walks away, and he dies in obscurity.

And so the novel Frankenstein, the story that it tells and the story of how it came to be written, has much to teach us about resilience.

And with that, I bid you resilience as you pursue your dreams. And to paraphrase Mary Shelley:

I bid you go forth and prosper.

More on Mary Shelley & Frankenstein.

- Frankenstein: The Creation Scene

- T. P Cooke’s Demon: The First Pop-Culture Frankenstein

- Not Your Universale Monster: The Hammer Frankenstein Series

- First Impressions: Discovering Frankenstein

- One Night in Geneva: The Birth of a Prosperous Progeny

- The Grave Misconception: The Textual Origins of Mary Shelley’s Monster

- On a Night in November: Shelley’s “Hideous Progeny” Comes Alive

Leave a Reply