The irregular tapping came from the other side of the sheet-metal wall that separated Paul’s and Harold’s cell from the totally enclosed tank for desperados next door.

The irregular tapping came from the other side of the sheet-metal wall that separated Paul’s and Harold’s cell from the totally enclosed tank for desperados next door.

Experimentally, Paul tapped on his side.

“Twenty-three—eight-fifteen,” came the reply. Paul recognized the schoolboy’s code: one for A, two for B … twenty-three—eight-fifteen” was “Who?”

That’s a rudimentary version of tap code (also known as knock code) depicted in Kurt Vonnegut’s Player Piano, a novel that a recent report on NPR called prescient in its anticipation of “the current state of AI and automation.” You’ll find it on page 306 of the Dial Press Trade Paperback edition, and it’s just one of a number of literary accounts of a code system introduced in this week’s installment of Prime Stage Mystery Theatre.

A more sophisticated version of the code system is depicted in Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon, a novel that The Modern Library ranked in the top ten of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. The passage below is from page 24 of Scribner’s hardcover edition. Like the scene in Vonnegut’s book, it takes place in a prison cell. The image below is from a 1955 NBC production starring Claude Rains, which aired on Producers Showcase in 1955.

The wall was thick, with poor resonance; he had to put his head close to it to hear clearly and at the same time he had to watch the spy hole. No. 402 had obviously had a lot of practice; he tapped distinctly and unhurriedly, probably with some hard object such as a pencil. While Rubashov was memorizing the numbers, he tried, being out of practice, to visualize the square of letters with the 25 compartments—five horizontal rows with five letters in each.

The wall was thick, with poor resonance; he had to put his head close to it to hear clearly and at the same time he had to watch the spy hole. No. 402 had obviously had a lot of practice; he tapped distinctly and unhurriedly, probably with some hard object such as a pencil. While Rubashov was memorizing the numbers, he tried, being out of practice, to visualize the square of letters with the 25 compartments—five horizontal rows with five letters in each.

The novels were first published in 1952 and 1941 respectively, but knock codes have been around for centuries, first developed in Ancient Greece and often used by prisoners (as noted in the above passages).

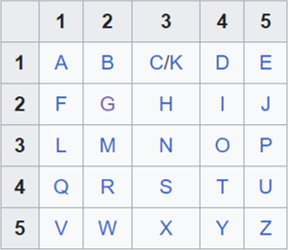

In English, the tap-code grid consists of 25 squares arranged evenly into five stacked rows, in which all but one of the squares contains a single letter, starting with A in the upper left and continuing through to Z in the lower right. The one exception, the middle square of the top row, contains both C and K, thus enabling the grid of 25 squares to accommodate the entire 26 letters of our Latin-based alphabet. This is the same grid described in Koestler’s book, as well as in the novel The Ash in Ælf Mystery that August LaFleur sites in this week’s installment of Mystery Theatre.

In English, the tap-code grid consists of 25 squares arranged evenly into five stacked rows, in which all but one of the squares contains a single letter, starting with A in the upper left and continuing through to Z in the lower right. The one exception, the middle square of the top row, contains both C and K, thus enabling the grid of 25 squares to accommodate the entire 26 letters of our Latin-based alphabet. This is the same grid described in Koestler’s book, as well as in the novel The Ash in Ælf Mystery that August LaFleur sites in this week’s installment of Mystery Theatre.

The graphic above is from Wikipedia.com.

Tap codes and the better-known dot-dash system Morse Code (click here for a chart) were among the topics that folks discussed at last weekend’s Mystery Theatre display in the lobby of The New Hazlett Theatre, where theatergoers attending the opening of The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe gathered to examine some of the clues presented in this month’s mystery.

Theatergoers and mystery fans attempt to crack the code at the Mystery Theatre Display in the New Hazlett Theatre.>>>

Theatergoers and mystery fans attempt to crack the code at the Mystery Theatre Display in the New Hazlett Theatre.>>>

But will either Morse or knock code decipher the sounds from Act I of “The Ælf in the Wardrobe”? Is it possible that some other tap code variation is being employed? Or could it be that the sounds aren’t codes at all?

Those are some of the questions we’ll be pondering this week. So keep your code charts handy, and get ready for some surprises when Mystery Theatre returns this Thursday with the second installment of “The Ælf in the Wardrobe.”

I’ll meet you there!

Leave a Reply